All Peoples

Isaiah 25:6-9

"The work of hope," writes Walter Brueggemann, "[is] an act of yielding in the present to the assurances given for God’s future.” We need hope because sometimes the present can feel pretty bleak. It may not look that way, but the celebration of All Saints is one of hope. Isn’t All Saints a remembrance of those who have died? Not many people would put hope and death together. In fact, most people hope not to die. Which is a little peculiar, given the odds. As of this moment, 100% of people who are living will eventually die. It is the inescapable fact of life. But it’s the kind of statistic that doesn’t really lend itself to hope. And yet, I will stand by this statement. This Sunday that we remember and celebrate those who have gone before us- loved ones, friends, and so many unknown to us- is one of hope.

Our reading from Isaiah is the first clue. We hear it at two moments in the church calendar: for All Saints, and on Easter Sunday. For those whose lives are framed by the gospel narrative and claimed by Christ, death and resurrection go hand in hand. We cannot talk about the one without mentioning the other. There can be no resurrection without death. And the good news in Jesus Christ is that there is nothing so dead that it cannot be raised to new life. No person, no relationship, no nation. That is the essence of Christian hope. It’s why when someone dies in our community, we don’t hold a funeral, or a memorial service, or even a celebration of life for them. We come together for a Service in Witness to the Resurrection as we give thanks to God for their life. We name our hope for those we love and for ourselves in the face of death.

Which brings us back to Brueggemann’s description of the work of hope. The present reality that must yield in this work of hope is a reality that is marked by death. It is a reality marked by uncertainty, and dread, and a future that feels very much in doubt. Collectively right now, it feels like we are holding our breath as a nation on the eve of this general election. After months, if not years, of politicking and campaigning each of the two major parties in this election have built it up such that whatever the result tens of millions of people will be devastated, tens of millions of our neighbors and fellow citizens will despair for the future of their country and what the result means. You would think this would go without saying in a church, but then even I have found myself sucked in to the hype machine, but our hope, our ultimate hope, is not dependent upon political outcomes. As we are cautioned in Psalm 146, “Do not put your trust in princes, in mortals, in whom there is no help.”

Whatever problems the present reality holds (or we think it holds) must yield to the assurances given for God’s future and not a future promised by our preferred candidate. Here in these few verses from the prophet Isaiah, we catch a glimpse of what God’s future looks like. It looks like a homecoming feast for all of humanity, with all the best food and the finest wine. And listen, this isn’t some pie in the sky hope that we have. These words, this vision comes after a judgement that is every bit as severe as these words are joyous. With clear eyes, God diagnoses the present reality of the people of Isael and Judah. It is a reality marked by the lawlessness of rogue nations like Assyria and Babylon who have laid waste to people far and wide. It is a reality in which the treacherous deal treacherously and the world is said to have fallen into the pit. It attempts to climb out only to be caught in a snare. From the chapter immediately preceding this one, God, through the prophet Isaiah, declares, “The earth staggers like a drunkard; it sways like a hut; it’s transgression lies heavy upon it, and it falls and will not rise again.” The assurance for God’s future is that a present reality incapable of righting itself, mired in the morass of division, hatred, distrust and retribution does not raise itself, cannot pull itself up by its bootstraps, but is and will be set right by God, and God alone. And when that happens it is a future in which the distinctions between the nations are no longer used to divide and separate. There are no more foreigners, not because they have been sent away and walled off, but have been welcomed at the feast God sets before all people regardless of their race, ethnicity, immigration status, political affiliation, social class, credit score, education level, work history, who they love, how they identify, or whether they prefer dogs or cats, or are just allergic and can’t have either. When we yield to this assurance of the future God envisions for us in the midst of a present reality in which transgression lies heavy upon us, the work of hope has the power to animate us, to strengthen us, to -yes- resurrect everything that we might otherwise leave for dead.

Last week we celebrated the reformation sparked by Martin Luther and the 95 theses he nailed in protest on the door of the church in Wittenburg, Germany. There is a quote attributed to Luther that may be apocryphal, but that speaks to this tension between the present reality and assurance of God’s future. “Even if I knew, the world would go to pieces tomorrow” Luther is quoted as saying, “I would still plant my apple tree today.” This is the work of hope that we are called to in our present reality with the threat of the world falling to pieces hanging over us every day.

The celebration of All Saints is more than a remembrance of those who have died, it is the work of hope. The present reality of our sadness over those who have died yields to an assurance about God’s future in which the shroud of death no longer separates us either, a future in which death is swallowed up once and for all and all the tears of this present reality are wiped away by the loving hand of God. There is something liberating about such a promise. Because the tears and the cause of them are real. And there is no shame in showing our emotion or feeling the grief of all that lies heavy upon us. We are saved from the expectation that we should stifle or hide our tears at all that has been lost, that we must put on a brave face or pretend that everything is just fine. And we are saved for a future in which God’s response to all that would make us cry is to wipe away our tears and invite us to the table God set for us and all who have gone before us.

This is what God does. This is who God is. God’s future is one in which all are made saints, not by the work of their own hands, or the totality of whatever virtue they may have achieved. The future doesn’t belong to who we elect, but who God elects from the beginning of time in Jesus Christ. All people are chosen and welcomed to the feast of God, set free from the shroud of death that hangs heavy on the world and made holy by the one who saves us from tears and calls us beloved.

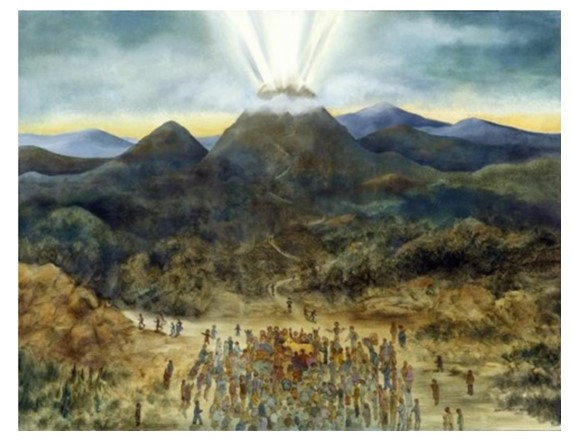

So, in this present reality, when it feels like the world may very well fall to pieces in the days to come, the work of hope calls us to look beyond what we can see to what we cannot. The work of hope directs our attention to the holy mountain of God on which all people are welcome, all people are fed, all people are set free, consoled and loved as God’s own. The work of hope calls us to plant our apple tree, just as the saints before us did. We are the fruit of their hope and we continue to live into that hope as we plant seeds of our own.