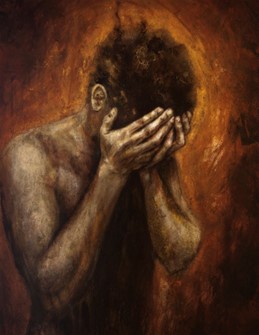

Darkness

Job 23:1-9, 16-17

Click here to view the full sermon video, titled "Darkness"

In his spoken word poem ‘Complainers,’ Rudy Francisco observes, “most people have no idea that silence and tragedy have the exact same address.” When tragedy first befell Job, when the first messenger arrived to tell him that his donkeys had been carried off by Sabeans who murdered his servants, and another messenger arrived to say that fire from God fell from the heavens to burn up his sheep and still more servants, and another messenger arrived to say that Chaldeans had raided and stolen his camels and killed still more servants, and a final messenger arrived to announced that a desert wind had collapsed the house where his children were eating and drinking wine, killing them all, we’re told Job tore his robe, fell to the ground and worshipped God. But then he was afflicted with sores from head to foot, and sat silently among the ashes. When his friends saw him they barely recognized him, then they sat on the ground with him, and for seven days and seven nights no one spoke a word to him, for they saw his suffering was very great.

That’s the part of this story that we know. But it’s a complicated story. Complicated by the wrinkle that all of this suffering comes about because of a dispute in the heavenly court of God. God boasts to the adversary about how upright and blameless Job is, and the adversary responds by suggesting that Job is this way because nothing bad has happened to him, he’s been blessed beyond measure. Take it all, it is suggested, and he will curse you to your face. When Job suffers loss upon loss and continues to worship, the adversary says, “Well, yes. People will give everything they have to save their own skin. Take his health and he’ll surely curse you.”

The setup should be our first clue that Job doesn’t exist in history. We don’t, as a general rule, have access the heavenly courts of God, or transcripts of the conversations that might transpire in such a place. That isn’t what Job is about. It’s about suffering. But more to the point, it is about innocent suffering. Meaningless suffering. Suffering like we’ve seen over the past month in the southeast, that has no other culprit than a strong wind created by the random atmospheric conditions of a warming planet. The book of Job addresses the perennial question that plagues people of faith, particularly when tragedy strikes. If God is all-loving and all-powerful, then why do bad things happen to good people? Libraries of books have been written in response to this paradoxical quandary. Many of which sound like the arguments and counter-arguments made by Job’s friends to explain his affliction. Invariably, the answers to the problem suffering creates for people who trust in God hedge on one of the three irreconcilable statements. Maybe, some argue, God isn’t as good as we’d like to believe. And anyway, who are we to impose our ideas of what is, or isn’t good on God. Isn’t that the origin of sin in the first place? Eating of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. That sort of thing can be pretty subjective after all. Or, others suggest that maybe God’s power is limited. Do we really expect God to micromanage all of creation? Could it be that God chooses to limit God’s power for the sake of the unfolding of creation? Maybe God’s lack of intervention is part of a larger design. Everything happens for a reason, you know. There has to be a reason. Or could it just be, as the Buddhist tradition teaches, that suffering is an illusion brought about by the disordered attachments of our ego? As a reluctant Calvinist, but a Calvinist just the same, I confess that I get hung up on the idea that bad things happen to “good” people because I’m not so sure anyone is all that good. All sin and fall short of the glory of God.

But none of these arguments or explanations are anything new. In fact, you can find shades of all of them in the bulk of the book of Job, which is largely made up of the discourse between Job and his friends as they try to explain why so much tragedy has befallen him. Still, in these verses we hear Job insist that he is innocent, that if he could just get an audience with God, he could plead his case and show that he doesn’t deserve any of it.

The truth is that some tragedies have a clear explanation, cause and effect. We know all kinds of behaviors and decisions that carry with them elevated risk. It’s why actuaries exist, to calculate and assess risk. The roof of the stadium where the Tampa Bay Rays play baseball is gone because hurricanes cause wind damage. North Carolina, like Houston before it, and any other number of cities hit by weather events, flooded because these storms carry and drop enormous amounts of rain. But why the tornado strikes and destroys one house while the one across the street emerges intact? We’ll never know. And it’s a dangerous game to say that God spared one person or family from a tragedy while another lost everything. Did God not spare them? Does God play favorites?

The answers to questions like that are shrouded in darkness. And to quote the outlaw William Munny to Sheriff Little Bill Dagget in the movie Unforgiven, “deserve’s got nothin’ to do with it.” Even when cause and effect come into play, it’s probably theologically unsound to suggest that anyone “deserves” a bad outcome any more than the person who goes unscathed has earned a reprieve.

Job says that no matter which direction he turns he cannot find, cannot see God. God is absent to him. And in the end, he isn’t sure which thought terrifies him more, coming into the full presence of God plead his case, or being without God altogether.

In his book Insurrection, Peter Rollins suggests that it isn’t just Jesus who dies on the cross, it is the whole religious project of managing our relationship with God in order to get wat we want and avoid what we don’t. Rollins goes so far as to suggest that in his cry of dereliction from Psalm 22, “My God, my God why have you forsaken me?” Jesus becomes an atheist. That is, Jesus stops believing in a god who never existed in the first place.

Maybe this is what happens to Job too. What vanishes in the darkness is neither Job, nor God, but a religion built on the faulty premise that the good are always rewarded and the bad always punished. The god who would acquit Job, who can be reasoned with and persuaded to save us from our suffering cannot be found because that is not who God is, no matter how much we wish it were so.

Instead, God is the one who speaks light into the void and calls forth creation. God is the one whose light continues to shine and the darkness does not overcome it. God is the one who brings light out of darkness on the first day of the week and brings what might otherwise be left for dead to new life.

I was talking with a friend of mine recently. Two and a half years ago he seemingly lost everything. Pushed to a breaking point by traumatic stress he lost control of his body, then his job, then his home, and eventually his marriage. He has known deep suffering. What struck me when I saw him was how much better he looked. As we talked, he said, “I’ve learned a lot about myself these past two years.” Then he added, “some things you can only learn through suffering.” I hated to hear it. I hated to think that it took something as dramatic and painful as what he went through to get to where he is now. But then it occurred to me that maybe that’s what Jesus meant when he said whoever wanted to be his disciple had to pick their cross to follow him. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t think Jesus wants us to invite suffering. Suffering finds us all eventually, one way or another. We don’t need to go looking for it. I don’t think it’s an illusion. It’s the reality that Jesus bears witness to on the cross.

We can make our case. We can try to reason our way out of it or explain it away and put on a happy face. We can cast blame it on others, or ourselves. We can wring our hands, protest our innocence, and proclaim our victimhood. Or in the silence of our deepest, most painful moments we can be still and know that God has not abandoned us after all, that there is no where that God is more present to us than when we are forced to let go of all our religious ideas about who God is supposed to be in order to encounter the God who truly is. As Barbara Brown Taylor writes in her book Learning to Walk in the Dark, “new life starts in the dark. Whether it is a seed in the ground, a baby in the womb, or Jesus in the tomb, it starts in the dark.”

It starts when we run out of answers, explanations, and even our bitter complaints and welcome the new thing that begins in the darkness of all that we do not know and cannot understand. Where we are held, nonetheless, by a love that refuses to let us go.