“RISK”

Luke 1:46-55

There is a classic quote about musical theater that I heard recently. On Broadway it’s said that, “when words aren’t enough, you sing. And when singing is not enough, you sing and dance.” The song and dance are the theatrical equivalent of a close-up shot on film. It’s the highest expression of emotion- whether the emotion is happiness, conflict, or love. In fact, it’s the connection of the voice to our emotions that makes singing such a vulnerable act. The instrument we are playing is our selves.

I’ve always loved that the first two chapters of Luke’s Gospel are filled with singing. Mary sings the song we heard in our scripture reading this morning. Shortly after, when John the Baptist is born, his father Zechariah, who has been struck silent through the whole of his wife Elizabeth’s pregnancy, bursts into song. Then there is the multitude of the heavenly host singing praise to God in the dark of night. Finally, when the baby Jesus is brought to the Temple for circumcision the righteous and devout Simeon takes him in his arms and sings. Four songs in two chapters. Some scholars describe these two chapters of birth narrative as the prologue to Luke. But I like to think of them as the overture.

The writer Frederick Buechner once described the season of Advent like the hush in a theater before the curtain rises. If you’re there to see a play the lights will dim and the curtain will rise. But if you’re there for a musical, the lights will dim and the curtain will stay put as the orchestra plays through a medley of the tunes that will be heard over the course of the story about to be told. Each one carries a different tone and rhythm, but together they provide the musical framework upon which the players will express emotions too powerful for simple speech.

For Mary it is the improbably bold declaration that echoes the exultant words of Hannah at the birth of Samuel, that God brings down the powerful of this world and lifts up the lowly; people of no account. Forgotten people. People like Hannah and Mary.

For Zechariah it is the revelation that his child is already a prophet of the Most High God declaring the tender mercy that breaks upon us, to shine on those who sit in darkness and to guide their feet in the way of peace.

For the heavenly host it is Glory to God and peace on earth to all.

And for Simeon it is the satisfaction of seeing God’s salvation in the flesh as a light not just for his own people, but for gentiles as well.

The high made low and the low made high. God’s essential mercy and forgiveness that prepares the way for new life. Glory to God and Peace on Earth. Salvation and light for those on the outside and those in the dark. These are the themes of good news and great joy on which the curtain of Luke’s gospel is about to rise. They sound so familiar because they are the soundtrack to our faith. And because they are so familiar, we can forget how risky it is to sing about any of it, how risky it is to give ourselves over to the hope these things represent and the God they seek to name. But perhaps of all the vocalists who give expression to the risky hope of the gospel, none is quite as vulnerable as Mary. Zechariah is a man of standing as a priest of the Temple. Simeon is at the end of his life. And the heavenly host? Well, they’re the heavenly host. Their position is uncontested.

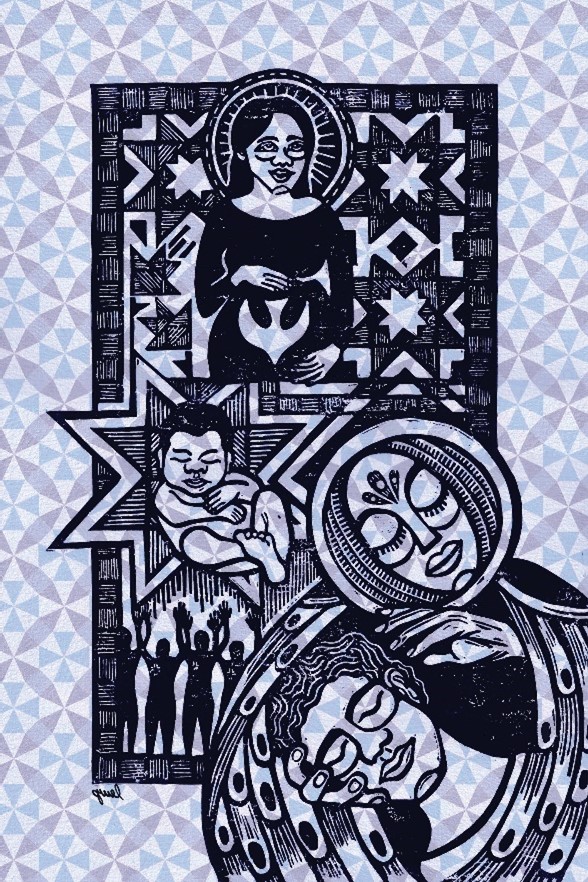

But Mary. Mary stands at the precipice. This past Sunday we had the privilege of hosting our interfaith friends from the Raindrop Foundation for lunch, thanks to the work of Marjorie Buck and the study and prayer group that meets on Tuesdays over zoom. The event featured a presentation by John Sitler, the religion teacher at Menaul School, about Mary. Although only mentioned a total of twelve times in the gospels and not at all beyond that in the rest of our scriptures, she has come to occupy significant imaginative space and an important role in both the Christian and Muslim faiths. On our recent trip to Spain our family took an outing to Montserrat where we visited the Benedictine monastery that is home to the statue of the Black Madonna. She sits behind protective glass with the Christ child in her lap. But there is a hole in that glass, just big enough for part of the globe held in Christ’s hand to stick through. Countless visitors a day line up to ascend the stairs leading to the statue, where they can touch the world that is held in Christ’s hand and pray for it. But before she was the queen of heaven, holding onto Christ as he holds onto the world. Before she was the intercessor who prayed for us sinners now and at the hour of our death, Mary was nothing more and nothing less than one more young woman in a forgotten part of the world. The legend of Mary has come to exalt her, but here in the home of her older cousin Elizabeth she is the recipient of a promise that sounds both impossible and revolutionary. It is a promise, “you have found favor… you will conceive and bear a son… he will be great… he will reign over the house of Jacob forever,” that leaves her perplexed, and confused, “how can this be,” and ultimately as ready as any teenager possibly could be to carry out something so strange and yet so wonderful. “Let it be with me according to your word.” Only later did we turn those words into some kind of confident consent, rather than its equally likely possibility: weary resignation.

It's often said that Mary is given a choice in the matter, but if you’ll re-read the passage carefully it looks like that plan has already been formulated when she’s informed about the role she’ll play, rather than asked. The fact is that we want to believe that we have far more say in the matter when it comes to the way God moves in and through our lives than we actually do. As the saying goes, life is what happens while we’re busy making other plans. Or more to the point, God is what happens while we’re making other plans.

Did Mary have a say in the matter? I don’t know. What I do know is that at some level she appears to understand two things. The first is that she has been chosen to carry and bear the Son of the Most High God. Now, is she favored by God because she is so very special and exalted and uniquely equipped for that role? Or is she so very special and exalted and uniquely equipped because of the favor God shows her? If it’s the former, then she becomes the impossible ideal to whom no woman, or any other person for that matter, will ever measure up. But if it is the latter… Well, that’s the second thing that Mary knows. And the thought of it is so overwhelming and the prospect of it so risky that she cannot help but sing about it. Sing about the God who looks and finds favor with the lowly, the forgotten, and the overlooked. Sing about the blessing that comes from hearing that, knowing that, and trusting that it is true. Because the Mighty One hasn’t just done great things for this lone, unwed teenager of marginal standing in the occupied territories of Palestine, The Mighty One does great things for all those who find themselves in exactly the same position as Mary. Compromised, scared, both expectant and terrified by what it all means. Because what it means is that all bets are off. What it means is that those who are so proud of their standing, or their wealth, or their power, or their position, or any other measure they think grants them some kind of privilege in this world will be SCATTERED in all they imagine in their hearts that they deserve, or are owed. God brings all those so-called powerful people down from the thrones of their and the world’s making, and instead raises up the lowly, the lost, the ones who have -metaphorically speaking- been left for dead. Even if she doesn’t know the details, here at the beginning Mary has caught a glimpse of the end that God has in mind, filling the hungry with goodness and sending those who are satisfied with the way things are away in the emptiness of all they would fill themselves with.

To sing of such things is a risk to be sure. Hope like that, trust in that, feels risky in a world in which the most dishonorable among us seem to get honored. But such is the revolutionary promise of the God who comes to us through the unlikeliest of people. People who find that they aren’t favored by God because they are necessarily extraordinary, but who do the extraordinary through the favor of God that is upon us, and for us, and ultimately with us.