Melchizedek

Hebrews 5:1-10

Click here to view the full sermon video, titled "Melchizedek"

You know you’re getting old when you throw out a pop culture reference, or mention an important historical figure only to be met by blank stares. Out of curiosity, I asked friends on Facebook about this phenomenon. One friend observed that his kids looked confused when he said to them, “party on Wayne.” Okay, so Wayne’s World may not be high art, but then I didn’t know the name of racecar driver Barney Oldfield when it was mentioned. Some of the answers truly boggled the mind: The Beatles, Tom Cruise, Walter Cronkite, John Denver, Stevie Nicks?? Every one of those names comes with its own set of memories and impressions. These names, their art, their music, alongside the history that goes with events like Sputnik or people like Merriweather Lewis and Aaron Burr. At least that last one is getting something of a resurgence thanks to the musical Hamilton. Still, it’s hard to imagine not knowing or recognizing the reference. Beside that, if people don’t know these names, then we have to explain in long form all that these names stand for and represent. But then again, our cultural shorthand is also how we insulate ourselves. It’s great when you’re in on the joke, or you get the reference. But behind the silent crickets of the uninitiated is the loneliness of being left out. A dear friend in this congregation who has since joined the church triumphant was insistent on this point when it came to the use of acronyms in our church business. Like any other organization the church is filled with the use of acronyms to shorten the mouthful of verbiage we’re prone to use in naming things. We call ourselves FPC and PC(USA) because First Presbyterian Church, of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America is a lot to type out and not everyone knows how to spell Presbyterian. USA is how we shorthand our country, and what we like to chant during the Olympics. We know what those letters stand for, but not everyone can tell you what UK, or UAE, PRC, or DPR stand for. Those are all countries, by the way. But beyond the acronyms, church and religion has it’s own vocabulary that can leave people scratching their heads and wondering just what it is that we’re talking about. And it isn’t always church outsiders who don’t understand. Every year when we train people called to the ministry of Elder, or Deacon, I explain just what the word Presbyterian means and what it tells us about the way we order our life as a church. Whether we’re talking about church, or business, the world of nations or the world of history and entertainment, it all adds up to create a culture. People like us do things like this, say things like this, use acronyms like this, know things like this. There’s power in that. The power of belonging to a shared story, shared knowledge, shared identity. And there’s a flip side to that power. The power to write people out of the story, to make them feel ignorant or stupid. You’re not from around here, are you? You must not be one of us.

That’s kind of how I feel reading this letter to the Hebrews sometimes. All of the bible really, in parts, but it’s fully evident in Hebrews. Now, we’re talking about the bible. This isn’t a book, it’s a library of books that are anywhere from three thousand to 1,900 years old. As Christians we’re taught that this our book, but then we get into it and while the terrain may be familiar in spots- we recognize this or that story- far more of it feels and sounds entirely foreign to us. And that’s because it is foreign. The whole thing is set some seven thousand miles away, in another time and culture. All of this is to say that when we heard a quote from the Psalms about the order of Melchizedek, and then heard it repeated in reference to Jesus, most of us likely stared blankly at the author without a clue of what he was talking about. Who the heck is Melchizedek, and what does he have to do with Jesus? Or what does Jesus have to do with him.

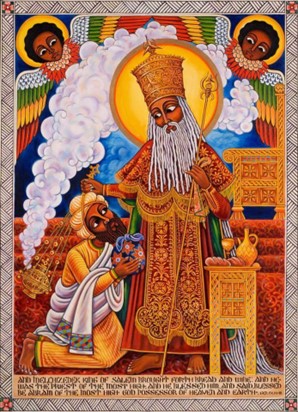

The answer is: it’s complicated. Throughout this letter the author quotes liberally from the Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures. Those scriptures refer to Melchizedek in exactly two places: what is quoted here, from Psalm 110, and the 14th chapter of Genesis. Scholarship is unclear which of these references came first. The former is a song to the king of Israel, presumably David. It belongs to a whole genre known as the “Royal Psalms.” It’s also the most frequently quoted psalm in Christian scripture. Jesus uses it to correct his critics. The book of Acts and Paul use it as an exaltation of Christ himself. As a royal psalm it speaks to an expectation and understanding of the Messiah; someone selected by God and anointed to serve as both priest and king. Which is where Melchizedek comes in. In Genesis, Melchizedek drops in after Abram rescues his nephew Lot from kidnappers. He is introduced as the King of Salem (thought to be a pre-cursor to the city that would later be known as Jerusalem), and a priest of God Most High. He shares bread and wine with Abram and blesses him in the name of God Most High. In return, Abram gives him a tenth of the spoils he plundered from Lot’s kidnappers. The suggestion is that this Melchizedek as both king and priest is the prototype that David will follow, and a foreshadow of Jesus as both priest and king.

Now, here’s the problem with all of this. As Americans, we don’t do kings. We just don’t. That’s pretty much at the heart of our Constitutional system. So, the way the bible talks about kingship and God as king doesn’t always land well with us. And as Presbyterians, we don’t do priests. They aren’t our jam. Instead of elevating one person to an exalted place in the church, we follow the lead of the letter 1 Peter which talks about the whole church as a royal priesthood. What Luther referred to as the priesthood of all believers.

Still, the author of this letter wants us to think of and understand Jesus in this way, in the way of Melchizedek as both priest and king. And it is entirely possible that rather than referring to an historic near-eastern ruler (there’s really no archeological evidence for such a person) that Melchizedek is an archetype. The name literally means, “my king is righteous,” or “the righteous one.” It’s a way of talking about someone who rules not from power, or authority, but from a right relationship with God, a priestly king whose role has less to do with ruling by force and more to with dealing gently with those they have been called by God to serve.

This is precisely why we look to Jesus as both the ultimate authority by which we seek to live and the one who stands before God on our behalf and before us on God’s behalf. He is our king, whose right relationship with God puts us right with God as well. He also shows us what righteous leadership looks like. It does not seek to glorify itself, but submits itself to God with humility and reverence. It doesn’t look to save itself and avoid suffering, but enters into and knows personally the full human condition of pain, loneliness and defeat.

And more than anything else it rejects the language of us and them that would divide and demean the person on the outside, the person who might not do things the way we do them, or understand things the way we understand them. Our great high priest is one who calls all believers into a priesthood of bridging the gaps, including everyone in the story we have to tell, and dealing gently with one another so that no one is left out.