Arise

Song of Solomon 2:8-13

Click here to view the full sermon video, titled "Arise"

When was the last time you attended a church service that was not a wedding where the featured scripture was from the Song of Solomon, or Song of Songs. Statistically speaking the odds are already unlikely. In the three-year cycle of readings that we tend to follow Sunday to Sunday, this book and these verses only come up once. That’s one in 156 Sundays. But there are four texts every Sunday, which increases it to one in 624. There is also an alternate set of first readings, not to mention special days around Holy Week and Christmas. And if it weren’t included this one time in the suggested cycle of readings, if you were to survey the landscape of worshipping communities that don’t follow the cycle, you might not hear it at all. Because let’s be honest, this text has something of a reputation. After all, it is one of only two of the sixty-six books that make up the Bible that the reformer John Calvin did NOT write a commentary on. The other book Calvin declined to write commentary on was the Revelation of John. Calvin considered the apocalyptic nature of Revelation too easy to misinterpret. That wasn’t the case with Song of Solomon. I suspect that this ancient Hebrew love poem was simply too racy for Calvin, and everyone else who saves it for marriage. You see the language of this book paints what can at times be an explicit picture of the sensual delights of human love. And that just downright embarrassing to talk about in church. I mean, is that sort of thing even appropriate to mention? Take a minute to absorb that reaction. We aren’t always comfortable talking about the full expression of human love in church. That can’t be right, can it? Honestly, I think it says more than we’d care to admit that we make so little room to hear this particular biblical witness in our time of worship.

Here is a scripture that celebrates the beauty of one of the most fundamental experiences of human life, and we hide behind our fig leaves, ashamed of what it has to offer us. What we have stepped back from celebrating has consequently become what one writer calls, “pornified.” Everywhere we turn this powerful expression of human love is being used through innuendo and graphic imagery to sell everything from hamburgers to deodorant. Even more, it has become a commodity in its own right. Internet pornography is perhaps the most profitable product in the world of e-commerce, and certainly the most prevalent. We live in a culture that is obsessed with who is doing what with whom and for how long; except in the church.

No, in the church we have taken the opposite approach, treating the human body and its attendant drives as something both scandalous and shameful. In reaction to the sexualization of the culture around us, the church likes to pretend that we don’t, or shouldn’t relate or react to one another physically. There is an old, old heresy for describing this body-averse way of living in the world, it’s called “Gnosticism.” Gnostic philosophy informs such non-canonical books like the Gospel of Judas that has a moment in the sun every generation or so. Among other things, the Gnostics regarded the human body to be a prison that they aspire to escape, an impediment to a kind of true spirituality that transcended this world of death and decay. While it was long ago denounced as incompatible with the good news of Jesus Christ, as far back as the second century, many of us have been influenced by it’s continued grip on religion that likes to portray a God who only grudgingly approves of physical desire as nothing more than a necessary evil for propagating the species.

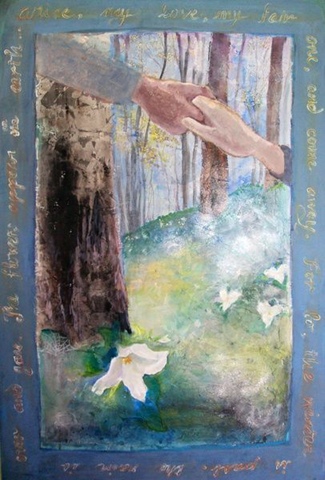

Too often we get caught in this false dichotomy between a worldly view in which erotic love is reduced and sold as something casual, recreational, and disposable, or a moralistic view in which such matters are corseted, shushed, and relegated to the shadows as a distasteful distraction to a truly spiritual life. Both of the options only serve to dehumanize us and consign us to a kind of living death; one by claiming we are nothing more than a collection of our own biological reactions and urges, the other by claiming that our true selves have little to do with the flesh and blood reality in which we live and move and have our being. In other words, both are a kind of sin that denies the fullness of what God intends for us as those who are created in God’s own image. That is what makes this Song of Solomon such good news. Because, while on its surface this poem is an ode to the passion shared between two young lovers, as scripture it is an invitation from God to experience a love that is neither simply physical, nor merely spiritual. It turns out that true love finds its wholeness in the union of the two- body and soul, the human and divine. Viewed through that lens, the words we hear from the lover in pursuit of the beloved take on a whole new meaning, “arise, my love, my fair one, and come away.” Suddenly we begin to better understand both the nature of our shared humanity and the character of our creator. We see that we are, as the boy Jonah puts it in the movie Sleepless in Seattle, M.F.E.O.- Made for each other. We are made to delight in one another. Whether that’s a meal or a cup of coffee shared with friends, a bike ride, or a simple walk along the Sandias, we are made to delight in the physical sensory experience of the world that God has made and so loves.

We do this all the time, when we take in the beauty of the mountains or the cottonwoods blazing gold along the Bosque, the sweep of this valley and the high desert. We do this when we breathe deep the smell of ozone in the aftermath of a monsoon rain, bask in the aroma of roasting chiles or fresh baked bread, or find comfort in the familiar scent of a loved one’s perfume. Here in this text is an invitation to the full sensory experience of being alive. “The flowers appear on the earth; the time of singing has come…” There are figs to taste and fragrant blossoms to smell. And there is the other, the beloved with whom we have been invited to share this bounty. If it is good, that is because the one who gives it- out creator God- is also good and desires for us to delight in this goodness. God intends for us to delight in the gift of our bodies as we are made for one another. It is a delight that carries echoes of the creation stories of Genesis. And it suggests that while the love expressed in the Song of Solomon is unbridled and passionate, it is a love that nonetheless has its origins in God. Which means that the love we are called to share and delight in finds its fullness in relation to God. Ultimately, we are able to love one another in this way, body and soul, because this is how God loves us. We aren’t used to thinking about God in this way. Talk to you friends. Ask them who God is, or more importantly where God is. The ones that believe in God will likely tell you that God is all-knowing, all-powerful, looking down on us from a holy and heavenly distance. Here again is the picture of a god removed from the carnal mess of the world we live in; interested in what we’re up to, but also fairly detached from the nitty gritty. Almost 20 years ago, after the earthquake and tsunami swept the coasts of southern Asia, a reporter called Untied Methodist Bishop Will Willimon and asked, “How do you reconcile this event with your belief in an all-powerful God who is in control of everything, who has set up natural laws.” Fortunately, Willimon had the presence of mind to ask, “Who told you that we believe in that kind of God? We believe God is love, that God’s love is vulnerable to us. We believe in the kind of God who came to us in Jesus. You talk as if we think God is a LAWYER! Our God is a LOVER!”

Not only is this song of songs a revelry in the blessedness of erotic human love, it is a celebration of the passion our loving God has for his beloved people. In the Jewish tradition, each of the five major feasts is marked by a reading of a different book from the writings of Hebrew scripture. Esther is read for the feast of Purim, to recount the events of that book. Ruth is read for the feast of Weeks during the time of harvest. Lamentations during the feast that marks the destruction of the temples. Ecclesiastes during the springtime feast of Booths in recognition of the time for planting. And the Song of Solomon is read in its entirety on the feast of Passover. Why Passover? Because it is a love song sung by Israel to her God. Just a few verses beyond where our reading this morning ended, the young woman sings, “my beloved is mine and I am his.” It echoes the promise of the covenant made with the people in the wilderness after being delivered from slavery in Egypt, “I will be your God, and you will be my people.” The kind of passionate love that is celebrated and sanctified in the verses of this ancient poem is the true love that God has for us. God loves us in the flesh. That’s what we confess happened in the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. It isn’t just the passion of Christ that we celebrate, it is the passion of God in Jesus Christ; God our lover whose desire for us became flesh to dwell among us full of grace and truth. It is an embodied love that claims us in the tactile waters of baptism on our skin, a love that invites us to the table to taste and see how truly love we are. Body and soul.