Absolom

2 Samuel 18:5-9, 15, 31-33

Click here to view the full sermon video, titled "Absolom"

You may be relieved to hear that today is the last Sunday of our sojourn through the story of David’s rise in the books of First and Second Samuel. It’s been a difficult journey at times, I know. For most people, if they have any awareness of David and David’s story at all, it comes in the form of something they learned as children in Sunday school, David and Goliath mostly. Few people know about the intimacy David shared with King Saul’s son Jonathan. If they know anything about the story of David and Bathsheba, it’s usually cast in the romantic technicolor glow of the 1961 movie starring Greogory Peck and Susan Hayward, not the far starker and more unsettling story that bears all the marks of a #metoo story about power, sex and coercion. Let alone the cover up and murder of Uriah. I have to shake my head, honestly, when I hear the invocation of so-called “biblical family values,” because a cursory knowledge of the bible and the families it depicts would disabuse anyone of the notion that theirs are the values to emulate or elevate. But then, maybe that’s the point. Too often we turn to biblical figures thinking that the inclusion of their stories in sacred text means that theirs is an example to follow. Instead, what we discover on page after page, story after story, generation upon generation are people who get it wrong far more often than they ever get it right. Or as an Old Testament professor observed about the book of Genesis, what we find is that the families of God are every bit the hot mess that our own families are. If anything, the bible gives us the courage to name that instead of pretending otherwise, instead of deciding that to be faithful means putting on a show so that no one will know how much we struggle. God knows. God has always known. Or to quote the wisdom of Ecclesiastes, there is nothing new under the sun. And God has yet to abandon God’s people.

What we just heard raises more questions that it could ever answer. That’s because it is the end of a long and painful story about the rift that develops between David and his son Absolom; a rift that subsequently threatens to swallow the whole of Israel. So perhaps the most pressing question is, “how did we get here?” How is it that David finds himself lamenting once again, only this time lamenting the death of his son.

This week in her online space known as The Corners, the writer and Lutheran pastor Nadia Bolz-Weber addressed a question from a reader that all of us inevitably ask at one time or another in our lives. Why? When things fall apart, when tragedy befalls us and we suffer some irrecoverable loss- of health, or work, or a relationship, or a loved one, we want to know why. Why is this happening to me? And when we’re not asking it about out own circumstances, we secretly wonder it about the misfortune that someone else is going through in the hope that naming some culprit will allow us to avoid their fate. We want to know who, or what is to blame, because blame creates the illusion of control. It’s an illusion because the only thing it allows us to control is our belief that by naming the source of misfortune, we can prevent it coming anywhere near us. It’s an illusion that politicians find useful because they can then present themselves as the one who will vanquish all those things we fear. The truth is that life can often be capricious. We want to believe that God is in full control of the mechanism, so that if something goes wrong then their must be a good reason for it, because – you know- God. But that really doesn’t seem to be how God, or the world works. Things can often change in a moment for no good reason. What we affirm in such moments is that we are not alone in them, that while there may be no good explanation- we do trust in the goodness of God who brings light out of darkness, hope out of chaos and life out of death.

But that isn’t the whole truth. Because sometimes there is a reason. A person who spends a lifetime smoking puts themselves at an elevated risk of developing lung cancer. That isn’t a punishment from God, it is the natural consequence of a choice that was made. At a deep level we know this. It’s probably why we go looking for someone, or something to blame even when there really isn’t anyone or anything to blame. Sometimes there is no good reason for the bad things that happen. But sometimes there very definitely is a reason. David’s grief is not simply the grief of a parent who has lost his child. David’s grief is the grief of a parent who knows that at some level he is to blame for the loss. But if David’s sin against Bathsheba and Uriah the Hittite was a sin of commission. The sin when it comes to Absolom is a sin of omission.

Strap in, because what goes down from chapter 13 to chapter 18 in the book of Second Samuel rivals anything you’ll find on a season of Game of Thrones. It all started when David’s firstborn son, Amnon fell in love with his half-sister, Tamar, Absolom’s sister. This was no simple crush. Amnon was so consumed by his feelings for Tamar that he followed the advice of a crafty friend who suggested how he might get her alone. He feigns illness and asks his father, David, to send Tamar to cook something and take care of him. When she arrives at his quarters, he sends all the servants away and forces himself upon her. She begs him not to. “Such a thing is not done in Israel,” she pleads, “do not do anything so vile. As for me,” she adds, “where could I carry my shame.” But her words are of no use. Amnon overpowers her and rapes her. And as soon as he has what he wants he despises her and has his servant throw her out of his house. As you might expect, word of the whole thing eventually got back to David- who, you’ll remember, is the one who sent Tamar to Amnon to begin with. He became very angry, we are told, but he would not punish his son Amnon, because he loved him. Perhaps it was the memory of his own guilt that prevented David from seeking justice for what was done to his daughter, Tamar. Perhaps he was afraid that punishing Amnon would make him the bad guy. Or perhaps, like so many powerful parents before him, he simply dismissed the violation of Tamar because he didn’t want to believe his beloved child could be capable of such a thing. Regardless, David’s failure to address the crime against Tamar would plant the seeds for all that comes after.

Absolom lures Amnon to a rich feast with all his other brothers. Absolom then commands his servants to kill Amnon in front of everyone. He then flees to a neighboring land for three years. Even so, David yearns for him and eventually Absolom is granted the right to return to Jerusalem and is forgiven by David. But Absolom is playing the long game against his father. He spends the next four years winning the hearts of the people and eventually forces David to flee Jerusalem. But he isn’t done. David leaves behind ten concubines to look after his house. And when Absolom takes the city, he also has a tent pitched on the roof of his father’s house so that he can go into to his father’s concubines in the sight of all Israel. Absolom then hatches a plan with his advisors to pursue David and his supporters. David’s spies try to get word to him but are forced to hide in a well when Absolom hears what they are up to. Eventually David get the message in time to escape with his people. In a sad kind of symbolism they retreat across the Jordan, leaving the land God had promised their ancestors. And it is all because David was unwilling to act on the violation of Absolom’s sister, Tamar.

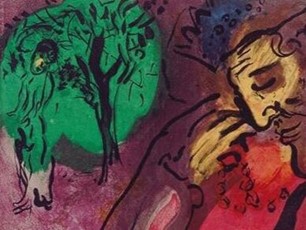

But even after all of that, David asks his most trusted commander to deal gently with Absolom. That is not what happens, and while Absolom hangs helpless, caught in the branches of a tree, he is killed. What are we to make of this story? Where is God in this biblical Game of Thrones? But then, maybe that is the point of it all. At one point, as David is fleeing Jerusalem, his supporters attempt to bring the ark, the ark of the covenant, with him. But David tells them not to. Not because he’s given up on God, or his own call as God’s anointed. No, David stops them because he sees how all of this has far less to do with God and far more to do with how David has failed- as both a father and a king. He trusts that if God wills it, he will see the ark again in Jerusalem where it belongs. But Absolom, Absolom is the embodiment of what happens when we turn a blind eye to the injustice under our own roofs, when we do what is easy instead of what is right for those who have no voice, no agency to make right the wrongs done to them. Absolom’s death brings an end to the threat to David’s rule, but it also brings an end to any chance David will have to make things right between the two of them. In fact, David says he would sacrifice his own life, take Absolom’s place if he could to make up for it all. David is not up to that. But the one who comes in his name, descended from this troubled family line, is up to it. And will do it. Thanks be to God.